Orchestra III from Connections 1983

Robert Frost - 'The Star-splitter'

"You know Orion always comes up sideways.

Throwing a leg up over our fence of mountains,

And rising on his hands, he looks in on me

Busy outdoors by lantern-light with something

I should have done by daylight, and indeed,

After the ground is frozen, I should have done

Before it froze, and a gust flings a handful

Of waste leaves at my smoky lantern chimney

To make fun of my way of doing things,

Or else fun of Orion's having caught me.

Has a man, I should like to ask, no rights

These forces are obliged to pay respect to?"

So Brad McLaughlin mingled reckless talk

Of heavenly stars with hugger-mugger farming,

Till having failed at hugger-mugger farming,

He burned his house down for the fire insurance

And spent the proceeds on a telescope

To satisfy a lifelong curiosity

About our place among the infinities.

"What do you want with one of those blame things?"

I asked him well beforehand. "Don't you get one!"

"Don't call it blamed; there isn't anything

More blameless in the sense of being less

A weapon in our human fight," he said.

"I'll have one if I sell my farm to buy it."

There where he moved the rocks to plow the ground

And plowed between the rocks he couldn't move,

Few farms changed hands; so rather than spend years

Trying to sell his farm and then not selling,

He burned his house down for the fire insurance

And bought the telescope with what it came to.

He had been heard to say by several:

"The best thing that we're put here for's to see;

The strongest thing that's given us to see with's

A telescope. Someone in every town

Seems to me owes it to the town to keep one.

In Littleton it may as well be me."

After such loose talk it was no surprise

When he did what he did and burned his house down.

Mean laughter went about the town that day

To let him know we weren't the least imposed on,

And he could wait—we'd see to him tomorrow.

But the first thing next morning we reflected

If one by one we counted people out

For the least sin, it wouldn't take us long

To get so we had no one left to live with.

For to be social is to be forgiving.

Our thief, the one who does our stealing from us,

We don't cut off from coming to church suppers,

But what we miss we go to him and ask for.

He promptly gives it back, that is if still

Uneaten, unworn out, or undisposed of.

It wouldn't do to be too hard on Brad

About his telescope. Beyond the age

Of being given one for Christmas gift,

He had to take the best way he knew how

To find himself in one. Well, all we said was

He took a strange thing to be roguish over.

Some sympathy was wasted on the house,

A good old-timer dating back along;

But a house isn't sentient; the house

Didn't feel anything. And if it did,

Why not regard it as a sacrifice,

And an old-fashioned sacrifice by fire,

Instead of a new-fashioned one at auction?

Out of a house and so out of a farm

At one stroke (of a match), Brad had to turn

To earn a living on the Concord railroad,

As under-ticket-agent at a station

Where his job, when he wasn't selling tickets,

Was setting out up track and down, not plants

As on a farm, but planets, evening stars

That varied in their hue from red to green.

He got a good glass for six hundred dollars.

His new job gave him leisure for stargazing.

Often he bid me come and have a look

Up the brass barrel, velvet black inside,

At a star quaking in the other end.

I recollect a night of broken clouds

And underfoot snow melted down to ice,

And melting further in the wind to mud.

Bradford and I had out the telescope.

We spread our two legs as it spread its three,

Pointed our thoughts the way we pointed it,

And standing at our leisure till the day broke,

Said some of the best things we ever said.

That telescope was christened the Star-Splitter,

Because it didn't do a thing but split

A star in two or three the way you split

A globule of quicksilver in your hand

With one stroke of your finger in the middle.

It's a star-splitter if there ever was one,

And ought to do some good if splitting stars

'Sa thing to be compared with splitting wood.

We've looked and looked, but after all where are we?

Do we know any better where we are,

And how it stands between the night tonight

And a man with a smoky lantern chimney?

How different from the way it ever stood?

Pattiann Rogers - The Origin of Order

Stellar dust has settled.

It is green underwater now in the leaves

Of the yellow crowfoot. Its vacancies are gathered together

Under pine litter as emerging flower of the pink arbutus.

It has gained the power to make itself again

In the bone-filled egg of osprey and teal.

One could say this toothpick grasshopper

Is a cloud of decayed nebula congealed and perching

On his female mating. The tortoise beetle,

Leaving the stripped veins of morning glory vines

Like licked bones, is a straw-colored swirl

Of clever gases.

At this moment there are dead stars seeing

Themselves as marsh and forest in the eyes

Of muskrat and shrew, disintegrated suns

Making songs all night long in the throats

Of crawfish frogs, in the rubbings and gratings

Of the red-legged locust. There are spirits of orbiting

Rock in the shells of pointed winkles

And apple snails, ghosts of extinct comets caught

In the leap of darting hare and bobcat, revolutions

Of rushing stone contained in the sound of these words.

The paths of the Pleiades and Coma clusters

Have been compelled to mathematics by the mind

Contemplating the nature of itself

In the motions of stars. The patterns

Of any starry summer night might be identical

To the summer heavens circling inside the skull.

I can feel time speeding now in all directions

Deeper and deeper into the black oblivion

Of the electrons directly behind my eyes.

Flesh of the sky, child of the sky, the mind

Has been obligated from the beginning

To create an ordered universe

As the only possible proof of its own inheritance.

——————————————-

Pattiann Rogers, “The Origin of Order” from Firekeeper: Selected Poems. Copyright © 2003 by Pattiann Rogers. Reprinted with the permission of Milkweed Editions, www.milkweed.org.

Source: Firekeeper: Selected Poems (Milkweed Editions, 2003)

The universe is overflowing with passion. For my own sake, I try with words to tap into that passion, that intense will-to-be, the tight hold against oblivion, the yes-power existing within all the manifestations of light.

Last word from this interview in 2008.

Pattiann Rogers - The Significance of Location

The cat has the chance to make the sunlight

Beautiful, to stop it and turn it immediately

Into black fur and motion, to take it

As shifting branch and brown feather

Into the back of the brain forever.

The cardinal has flown the sun in red

Through the oak forest to the lawn.

The finch has caught it in yellow

And taken it among the thorns. By the spider

It has been bound tightly and tied

In an eight-stringed knot.

The sun has been intercepted in its one

Basic state and changed to a million varieties

Of green stick and tassel. It has been broken

Into pieces by glass rings, by mist

Over the river. Its heat

Has been given the board fence for body,

The desert rock for fact. On winter hills

It has been laid down in white like a martyr.

This afternoon we could spread gold scarves

Clear across the field and say in truth,

"Sun you are silk."

Imagine the sun totally isolated,

Its brightness shot in continuous streaks straight out

Into the black, never arrested,

Never once being made light.

Someone should take note

Of how the earth has saved the sun from oblivion.

——————————-

Pattiann Rogers, "The Significance of Location" from Firekeeper. Copyright © 2005 by Pattiann Rogers. Reprinted by permission of Milkweed Editions.

Source: Firekeeper (Milkweed Editions, 2005)

Hilma af Klint

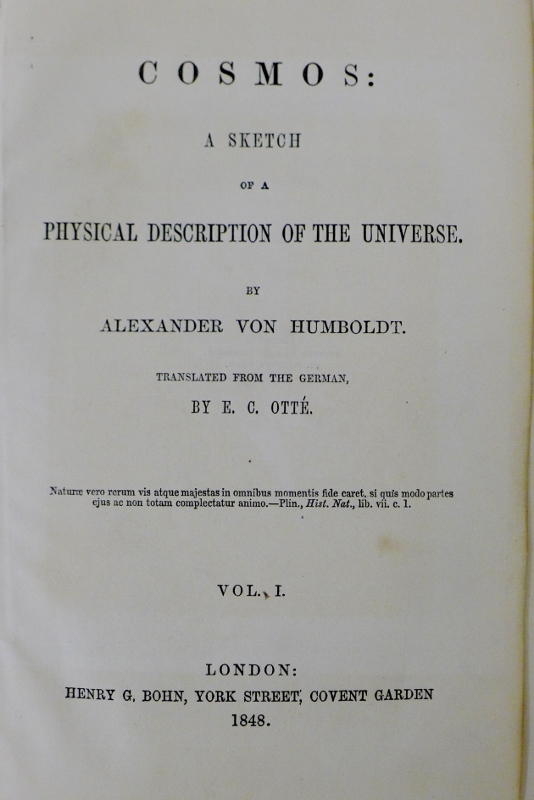

Alexander Humboldt on describing nature.

An extract from Volume II, Cosmos.

"Descriptions of nature, I would again observe, may be defined with sufficient sharpened scientific accuracy, without on that account being deprived of the vivyfying breath of imagination. The poetic element must emanate from the intuitive perception of the connection between the sensuous and the intellectual, and of the universality and reciprocal limitation and unity of all the vital forms of nature. The more elevated the subject, the more carefully should all external adornments of diction be avoided. The true effect of a picture of nature depends on its composition; every attempt at an artificial appeal from the author must therefore necessarily exert a disturbing influence. He who familiar with the great works of antiquity, and secure in the posession of the riches of his native language, knows how to represent with simplicity of individualising truth that which he has received from his own contemplation, will not fail in producing the impression he seeks to convey;

for in describing the boundlessness of nature, and not the limited circuit of his own mind, he is enabled to leave to others unfettered freedom of feeling."